Michael's Story

TELL US a LITTLE ABOUT YOUR TRAUMA STORY

“Don’t get up you were hit by a car…,” fluttering eyelids, jolting me out of the empty darkness. Blurred green, yellow, blue, and gray colors. The wind faintly whispered “You were biking in Fulshear….” I quickly sank back into the dark, empty void.

Minutes before 8:30am on July 11, 2015, I rode my road bicycle into Fulshear Texas, a then-small rural town just outside the western-edge of Houston. It is a route that I had done dozens of times over the past three years as I trained for Ironman triathlons and the annual MS 150. I felt exceptionally strong after two-hours. The coolish morning temperature was a relief for early July. The light and warmth of the sun rays bolstered my spirit.. A few groups of bikers passed heading the opposite direction. There were virtual a handful of cars on the road. What a perfect day to resume bike training for the November Half Ironman in Austin, I recall thinking.

Passing the American flag next to the Fulshear Post Office, I remembered my appointment later in the morning to help my daughter with her college bank account for her first year in college. I increased my tempo to 20 mph, as recorded on my Garmin Triathlon watch, in a sprint to the only stop light in town a mere mile down the carless road.

A blue Town and Country minivan sped up on the opposite side of the road. The driver quickly turned left onto 4th Street, one block south of the post office. Seeing bikers, she was trying to “beat the bikers” as she shakenly confessed to the police later. She turned the minivan at roughly 30 mph right directly in front of the path of my bike.

“Oh SHIT!,” I yelled. Instincts kicked in as I attempted to maneuver away from the car once I realized a car had suddenly turned in front of me. As we collided, I instinctively put down my left shoulder for the hit, as I had been taught by my grade-school and high-school football coaches.

It was a direct impact on me. The front left end of my bike and the left side of my body struck the minivan. I flew off the bike smashing my left shoulder, arm and ribs into the right front side quarter panel and shattering the front window shield with my left upper extremities. The passenger side mirror broke. Metal and glass cut deep into my left arm muscles. My bike snapped in two. Glass engraved scratches on my protective safety sun glasses, which saved my eyes, as it ripped a huge gash above my left eyebrow and forehead. I flung off the van and smacked the ground into the empty, dark void of a concussion.

I should’ve died.

Yet, I survived.

Fortunately, road gravel slid into the exposed deep cuts in arm, and somehow by the fate of God, clogged the gash to my brachial artery. This clogging prevented my death from exsanguination - the loss of blood.

The man kneeling next to me saved my life. He was a former Army medic who was biking in the area. Another biker summoned him to action as he rested at the gas station next to the stop light. Without a hesitation, he raced his bike a few blocks to me. He stabilized me until the local emergency services arrived. He also had some call my wife, who rushed over the seven miles with my two daughters to help me.

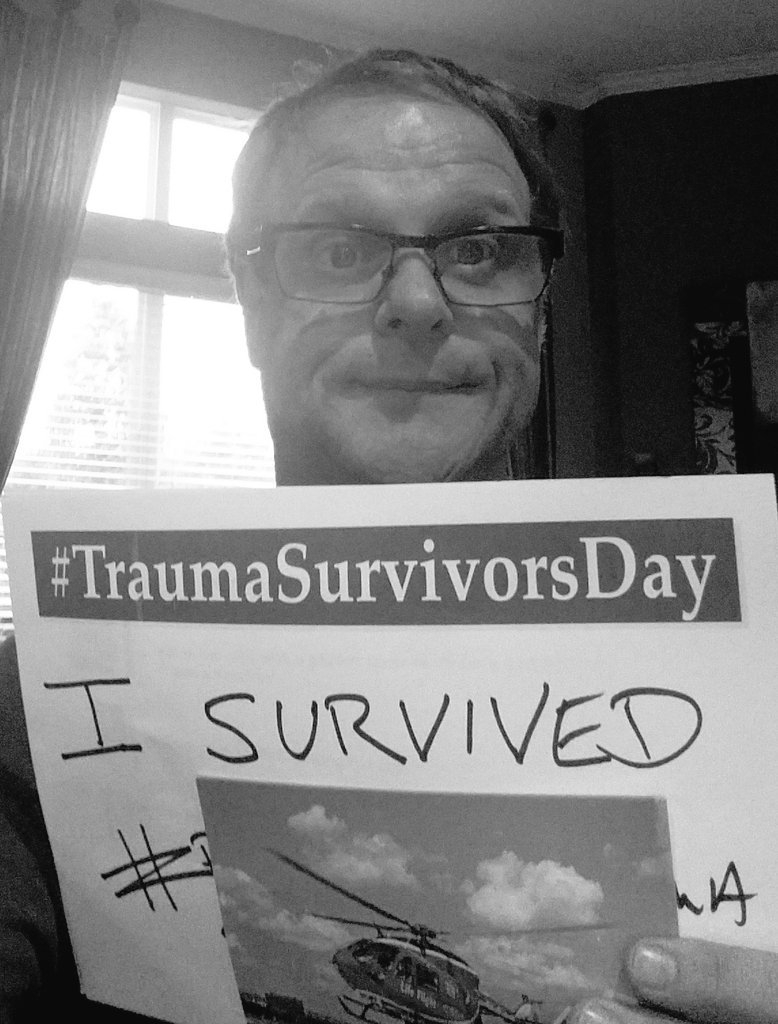

I broke nine ribs and fractured my left knee and left shoulder blade. Lacerations covered my left arm with the deepest cuts in my upper arm muscles. I had a concussion. My left lung collapsed, punctured from one or several of the nine broken ribs. The medics feared damage to my spine, brain, and other internal organs. Their concerns over internal injuries got me a ticket for a 35-mile helicopter ride to the Hermann Memorial Trauma Center near downtown Houston. Memorial Hermann Trauma Center classified my injuries as a Level 2 Trauma.

WHAT WAS RECOVERY LIKE?

The initial recovery in the hospital ICU and subsequent home medical care basically was a matter or survival. My left side of my body was immobile as I was unable to move my leg or lift my arm. My second night after regaining consciousness, I turned to the night nurse who introduced herself as Nurse G and broke out crying asking “Why did this happen to me?” She gestured to the nurse aid to pause, just allowing me to cry. This simple act of compassion did so much to bolster my sense to have a semblance of control over myself. The doctors, physical therapists, nurses, and countless others challenged me with breathing exercises to strengthen my lung and even to get out of bed to sit on a chair. I went further and had my wife write on the medical communication board “start training for an ironman” as one of my goals. Within a week, I was home bound where the real challenges began.

My recovery story really is a struggle of living with the unthinkable every day The accident traumatized me. I should be dead. So, how have I reacted to unthinkable trauma? I got pretty acute post-traumatic stress. I felt sad, depressed, and helpless. Sleep evaded me. I plunged down into a downward spiral of depression, hopelessness, and anxiety. When I could start driving again, I would drive to the scene of the accident and sit the car crying over and over. The pain damaged my mental state. . It never really goes away no matter how well-adjusted I became. It remains a lingering open wound.

Oddly, PTSD hit the hardest as my physical recovery improved and my medical help stopped six months after the accident. My orthopedic specialists gave me approval to start strenuous exercising. My shoulder blade was healing nicely. I was able to lift my arm close to 80% range. I stopped my physical therapy shortly thereafter. I needed to own my recovery. Driving home after my last physical therapy, I cried in joy. I would be able to achieve the goal I wrote on the pain chart in hospital to return to my Ironman training. I cried out “I am Ironman tough” over and over. I felt the world was mine to conquer. Tears of joy.

Then the nasty side of PTSD struck and it struck hard. The silent killer rose its ugly head. I became depressed. I wanted to be alone. I snapped at anything or person who caused me stress. It was ugly. At home, I hid this from my family. I barely slept 2-3 hours each night. I had been sleeping on couches and chairs due to the physical discomfort in my shoulder and ribs. Now, anxiety and flashbacks jerked me awake. I distracted myself with my family history, sometimes devoting 3-4 hours in the middle of the night. I was drifting in a PTSD river filled with traumatized memories, emotions, and fears. Like other times in my life, I floated away from reality.

I felt lost. I did not know what to do and whom could help. Several psychologists listened, yet just did not get it. I just needed some people to talk to. I realized I needed a support group.

What I found was a network of trauma survivors. On Wednesday May 18, Memorial Hermann Life Flight posted on Facebook information on National Trauma Survivor day. Within a few weeks, I had two phone discussions with other trauma survivors and counselors from the American Trauma Society. When we talked, I instinctively felt they got it. I understood them. They understood me. For the first time, I felt relieved that I was experiencing typical PTSD responses. I finally found some compassionate understanding. I realized I was living with a new norm. There was no going back.

My hope for the future began to return. I began taking almost daily PTSD self-assessments to track my improvements. My physician confirmed the severity with a military PTSD assessment of PTSD. I attended a Church retreat to center my life back in religion. I openly cried in front of a counselor for the first time.

I had turned a corner. Eighteen months after the accident, I completed the Austin Half-Marathon. As I struggled with cramping left legs and pulsating rib pain, I pause on top of hill and struggled with the choice should I drop out or should I just take one step at a time and complete the race. I thought of the man who helped me as laid in pool of blood, I thought of Nurse G, and my physical therapist Camile. I couldn’t quit, I could finish. I did finish, after which I just hugged my wife whispering “I did it.”

The struggle since then continues as I have grown to accept the these triggers, night terrors, and physical pains are just part of my new norm.

Why did you want to get involved with the TSN program? Or Why do you want to share your story with other survivors/loved ones?

My passion to help others by sharing my story is that I want to be like the two individuals who sparked hope and optimism during a bleak time in my life. PTSD is something I live with every day, and the way I have learned to cope with may be a seed that can help others.